Charlevoix: A History of Visiting Boats

By David L. Miles Curator, Museum at Harsha House, Charlevoix Historical Society

The cover of this year’s Docklines shows three pleasure craft leaving Charlevoix’s Round Lake harbor, passing through an opened bridge, which incidentally turned 75 years old in 2024.

This is certainly not an unusual sight during the temperate seasons. But where have they just been? Perhaps they were tied up somewhere in the city yacht basin along the western edge of Round Lake, just below downtown Bridge Street/ US31, the town’s main artery and the only way through town. Maybe they’re coming from one of the marinas on Lake Charlevoix. Wherever they have just been, they are leaving what has long been regarded, by both pleasure and commercial mariners, as one of the best naturally protected harbors in the country. In 1869, both channels were cut to connect Lake Charlevoix and Round Lake to Lake Michigan and the inland seas for the first time. Then the world began to beat a pathway to Charlevoix’s door. This cutting caused an economic explosion, which surpassed the wildest dreams of the Charlevoix Harbor & River Improvement Company. This determined group accomplished the channels’ creation for less than $1,500. Schooners, passenger steamers of all sizes, wood and metal lake freighters, tugs used for general haulage and fishing, Coast Guard boats, lumber hookers, government vessels, naphtha launches, and resorter sailboats poured in during the first few decades. By 1897, the Charlevoix Sentinel newspaper reported that more maritime tonnage was now passing through the waters of Charlevoix than any other port on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. But motorized smaller pleasure craft? Not so much, in the beginning. That industry took a while to get started. Round Lake was chockablock with maritime commercial enterprises that occupied almost every inch of shoreline. The town’s two resorts, the Belvedere and Chicago Clubs, provided much of the pleasure dockage and boathouse areas for their own members. It wasn’t until the mid-1920s that the city began to receive requests for pleasure docking from outsiders and wisely acted upon it, if on a very small scale. The first section of Round Lake to be designated solely for small craft was at its southwest corner between Antrim and Mason Streets, next to today’s Ward Bros. Boats, Inc. fueling location.

This A once busy commercial hub had gradually disintegrated, even before the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. Round Lake was beginning to change with the times. Here, a grand total of five new docks, eccentrically spaced and of varying sizes, provided moorage for ten boats around 1925-1926. Now, boaters could enjoy the privilege of driving down to their dock, parking, taking a sail or cruise, returning, and driving back up to Bridge Street. Not long after the docks were installed, the city replaced the initial rough roadway with an actual block-long paved road with curbing. The area above this, the east 400 block between the two streets, was transformed into a park complete with a bandstand. It wasn’t until the complete development of East Park, in the depth of the Depression, that anything more happened. After a hotel in the east 300 block of Bridge Street burned in 1935, the city saw the view through the gap and realized the potential for a magnificent park that would ideally stretch from the channel bridge, along all four downtown blocks, to Antrim Street. After a successful fundraising project, which involved both locals and resorters, all but two of that block’s decrepit commercial buildings were purchased and taken out, freeing up the land behind them. From 1937 to 1939, the crown jewel of Charlevoix’s park system transformed the land, efficient spaces for over thirty boats were added, and the original five docks were refurbished. A four-block park never did come into being, but what did certainly changed downtown and brought uncounted hundreds of additional pleasure boaters into the heart of town. However, over the ensuing decades, as the demand for dockage steadily increased, all this development became woefully inadequate. The constant upkeep of an increasingly scruffy park and crumbling amenities, plus the replacement of stationary docks that battled the lakes’ high/low water level cycles, was simply not enough. In the late 1990s, a committee of determined citizens laid the groundwork for a complete redesign of the park and yacht basin. They didn’t let one cubic inch escape their inspection and decision making. After nine years, it all came together. Between 2007 and 2009, the yacht basin was radically reconfigured with floating docks, which would accommodate over twice the number of boats. A large, acoustically perfect performance pavilion was erected, and the entire two blocks were relandscaped into something spectacular. The American Planning Association of Chicago and Washington, D. C. was so impressed with what Charlevoix had accomplished that, on its 2009 annual honors list of ten, in company with Lincoln Park in Chicago and the squares of Savannah, Georgia, Charlevoix’s East Park/ yacht basin complex was named one of the ten best public spaces in the United States.

BUT HOW WERE LARGER VESSELS HANDLED?

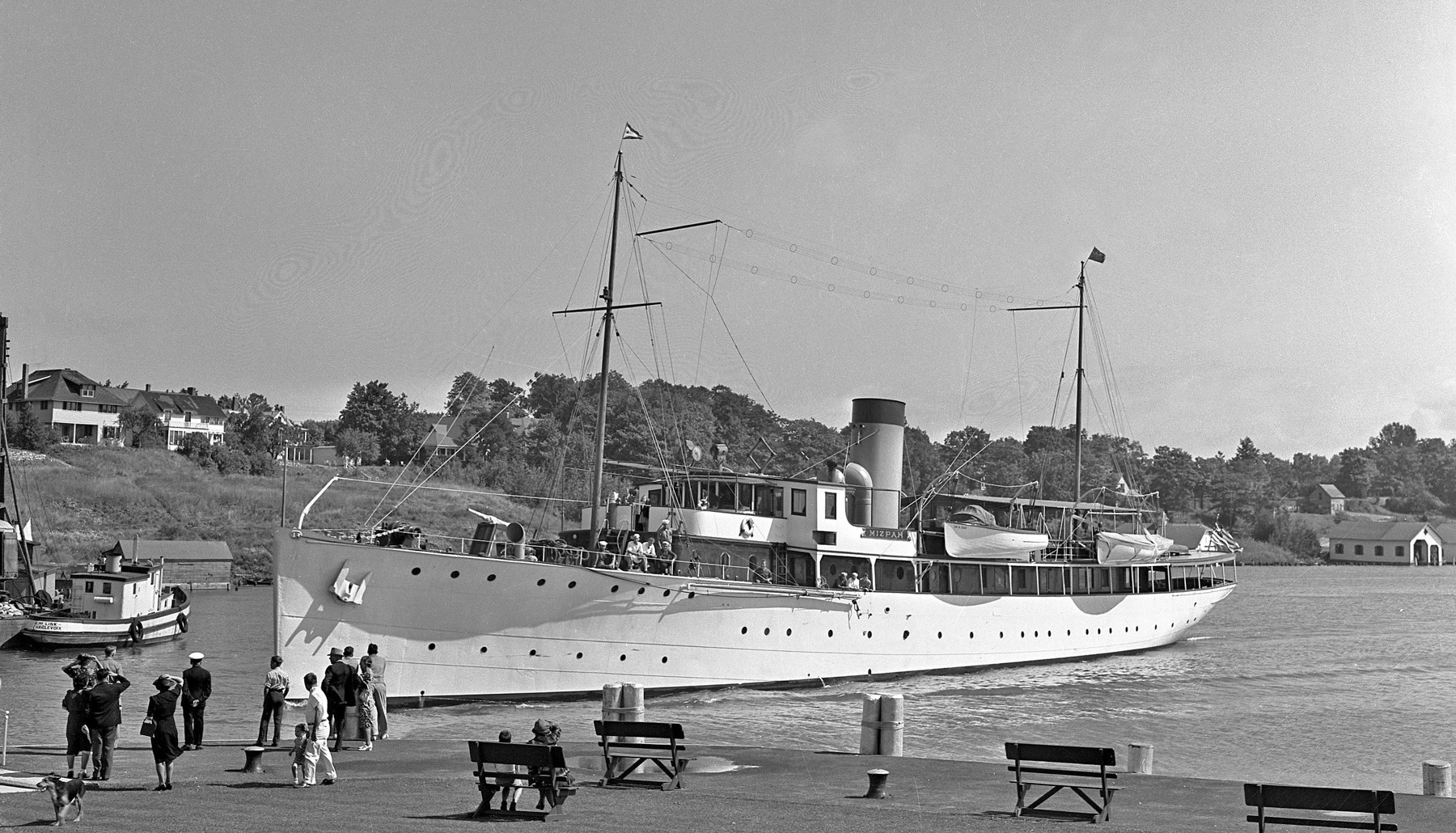

Charlevoix certainly has seen its share of some of the grandest yachts ever to sail the Great Lakes and the world’s oceans. Seagram’s, L’Oreal, and IBM vessels have been visitors, as were those of Ivana Trump and Kid Rock. A few, like those registered in the Cayman Islands, have come in with strict orders not to divulge ownership or origin to anyone. The Dorothea began life as an intended palatial yacht in 1898. Its owner died before it could be finished. The federal government bought the vessel and completed it as a “torpedo boat-destroyer,” which saw duty as a patrol boat off the coast of Cuba during the Spanish-American war. In 1901, the state of Illinois asked the government for a vessel that could be used as a training ship for its naval militia. The Dorothea was offered, and it served during the summers in Charlevoix through 1909, after which another boat took its place. It was quite a sight to see this beauty depart from its center-of-Round Lake mooring into Lake Charlevoix for maneuvers, with its entire cadet crew formally lined up on both sides of the boat, all clad in their training uniforms and white hats. The largest private yacht on the Great Lakes, the 225-foot Venetia stayed for a grand total of two days in July 1928. Owned by James Fairplay of Midland, Ontario, the vessel was so big it couldn’t be accommodated in Round Lake. The Venetia had to sail in, turn around, and come back down the lower channel to tie up against the cement revetment close to the former Coast Guard station. Fairplay was on an extensive excursion with some gentlemen friends. They stopped here to try out the recently completed golf course of Charlevoix’s Belvedere Club resort association, quickly recognized as one of the best in the country. So impressed was Fairplay with both the town and the course that he expressed the wish to return later in the season for an indefinite length of time. It’s not known if he made good on his intention. Mizpah, the Hebrew word for “watchtower,” became the name of a vessel originally built by the Navy in 1926 as part of a new class of destroyers. However, the 185-footer was never commissioned, due to an international agreement to limit the sizes of the world’s navies. Three years later, it came into the hands of its third owner, Eugene McDonald of Chicago, head of the Zenith Radio Corporation, who gave the boat its name. “Mizpah” appears in Genesis 31:44-54 in the line “the Lord watches between me and thee, when we are absent one from another.” The boat was one of the largest luxury yachts on the Great Lakes, sporting gold-plated doorknobs and carrying a crew of twenty-seven. Charlevoix was the Mizpah’s base for many summers.

In 1932, it sailed in with several guests aboard, one of them sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who was taking a break from carving the presidential heads on Mount Rushmore. McDonald used the boat to test a rudimentary form of radar off Cocos Island near Costa Rica, and found it to perhaps have a future, little knowing the importance and scope of what was to follow. And the greatest of them all, the incomparable 192-foot Sylvia was the fifth in a series of vessels named after the wife of Logan Thompson, head of the Champion Coated Paper Company of Ohio and a member of the Belvedere Club. Completed on spec in Maine in 1930 as one of five identical sisters, the boat had its own dock on Round Lake at the club. For some reason, Thompson dropped the Roman numeral V from its name. So svelte and graceful were the lines of the Sylvia, that when it traveled back and forth across Round Lake, it appeared not to be cutting through the water, but gliding atop it. Both pedestrian and vehicular traffic on Bridge Street came to a hypnotized halt whenever the boat made an appearance. Sensing what was about to explode in an increasingly troubled world, Thompson donated his treasured yacht seven months before Pearl Harbor occurred in late 1941. He knew all boats of this kind would be confiscated for war duty should hostilities erupt, so he willingly, patriotically did his duty in advance. In April that year, the Sylvia, with the Stars and Stripes painted mid-hull on both sides, made its farewell tour of Lake Charlevoix before heading out to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for gutting and conversion, never to be seen in Charlevoix again. During the war, it served as the Patrol Yacht Tourmaline. After the war, the boat was sold for the Greek war relief effort in 1946. Used as a freighter/passenger vessel in the Aegean, it was first named the Adelphic and later the Kyknos. The last trace of the stunning Sylvia was the mention of it being scrapped in 1979. This is some of what Charlevoix has witnessed over the past century, during which pleasure boating grew into a major industry, producing vessels of all sizes and many types. The town is not able to have the largest marina in the immediate region, mainly because there is little, if any, room to expand in Round Lake. To do so would compromise the integrity of what Charlevoix is so fortunate to possess–the beautiful blessing that nature alone has bestowed upon it. Reports have reached the Charlevoix Historical Society of first-time visitors being gobsmacked at the first sight of Round Lake, whether arriving by vehicle or boat. “We have traveled all over the world, and we have never seen anything to match this,” they declare. Well, a little justified bragging might be called for right here. In 2021, USHarbors.com declared Charlevoix’s Round Lake to be the be the best harbor in the United States.